This essay is primarily in reaction to discussions around pessimism among climate activists, where due to the scale of the climate problem it is reasonable to be pessimistic towards any given strategy. However, the framework provided is written in the abstract and can be applied to how pessimism is approached more broadly. In a future essay we will apply this framework specifically to the climate problem.

We often hesitate to critique how things are done or to evaluate strategies that we are going to participate in. When asked why, we say that it feels wrong to engage in discussions that may demotivate and prevent action. We worry about overthinking, inducing ‘choice paralysis,’ and fumbling opportunities with indecision. Often we are told it is better to not question plans if we can’t suggest better alternatives. Further, we’re not sure if it is our place to engage in critical discussion that may demotivate, especially if we lack specific ‘expertise.’ Anything leading to pessimism can feel morally wrong, whereas optimism is seemingly always virtuous. In general, we often feel that the biggest hurdle to success is maintaining action. Therefore, it seems we ought to avoid anything that risks pessimism because it may cause inaction.

Yet pessimism can result from a reasonable evaluation of strategies, especially when taking on powerful interests or attempting to achieve something difficult. To avoid it, one would have to avoid reason itself. Avoidance costs us honest engagement, exploration, and many other essential features of open discussions. Furthermore, efforts to avoid discussion can feel inauthentic, a complaint made towards many groups. This high cost is rarely admitted because we tend to only focus on the effect of pessimism on action, where avoiding it is immediately beneficial, and its long-term effects are unclear. The more we avoid pessimism the less open our discussions can be. Yet we commonly encourage avoiding pessimism while simultaneously advocating for open discussions without contending with the conflict between the two. This has led to the blunting of discourse. Worst of all, it has resulted in a general hesitancy towards understanding what actions make sense to us.

Given these high costs, why is it common to invoke caution towards pessimism and critical discussion?

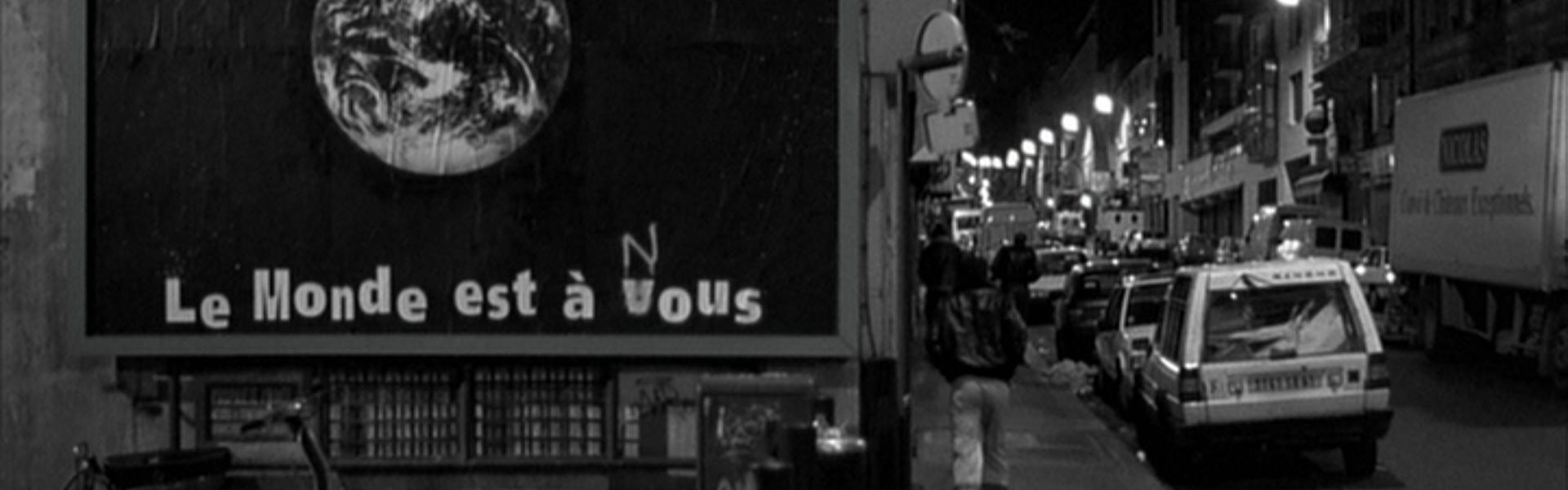

They’d love it if we gave up

A potential explanation is that caution is necessary due to malevolent outside actors. Those who have power over others may gain from people giving up on plans that can change the conditions of their own lives. Anyone that wants to stop your plans, or way of life, would love it if you were paralyzed by pessimism. Therefore, they are incentivized to make it seem like your goals are impossible. They may try to convince you that your nature (or even human nature) would prevent you from achieving your goals. Therefore, given the powerlessness that people experience in so many aspects of life, it is no surprise that people guard against pessimism.

This guardedness is not intended to avoid evaluation or reason, but to protect the group's ability to reason internally. The external environment may be so toxic, so filled with disinformation and threats, that extraordinary precaution is necessary in order to trust one’s own thoughts and the thoughts of others. This justifies serious hesitations prior to any discussion, or even reflection, on strategy.

However, one’s evaluation is not always manipulated in the direction of pessimism. If those that want you to fail see you going down a dead end, they will happily fan your flames and even shield you from any pessimism that may come your way. Given that we tend to believe in the strategies that we have committed to, this form of manipulation can be particularly insidious. Whereas bad-faith pessimism can justify hesitation towards critical discussions, bad-faith optimism should lead to prioritizing critical discussions. Thus, the effects of ill-intentioned outside actors does not necessarily lead to avoidance of pessimism; therefore, it remains unclear to what extent ill-intentioned outside actors are an explanatory factor for the hesitancy towards critical discussions.

Furthermore, if outside actors were the main explanatory factor, we would expect to see precautions that still allow space for lively discussion. This suggests that those precautions that discourage pessimism are not mainly to protect our discussion from outside influence, but rather to direct our discussions away from causing demotivation. Therefore, another explanation is needed to explain why this guardedness exists.

Action as the ultimate good (or fear of the pessimism of the intellect)

Many groups today are largely defined by activities or by a specific set of actions. A consequence of a group being defined by activities is that if a member loses interest or no longer believes in the activities, they will have to leave the group entirely. Therefore, both the members and the group benefit from avoiding whatever may result in decreased interest. (Side note: this is what makes hobby groups so stagnant sometimes. This also applies to an individual: for example, if you define yourself through your activities, then in order to maintain your identity it becomes important to not risk losing interest in those activities.) A strategy or activity may be appropriate in some situations and not others; therefore, activity-based groups may have short lifespans in contexts that are rapidly changing.

Such activity-based groups are naturally brittle to pessimism. If reflection results in a member concluding that the actions or strategies of the group could never reach their goals, then that individual will either have to leave the group or avoid that type of reflection.

However, this is not a major problem for all action-based groups. For example, those that take on easy-to-achieve strategies do not have to worry about pessimism. They are comfortable in supporting discussions that critique and compare strategies, because the current strategies are already likely to work. Thus, they are confident that faults that are detected in strategies will not result in pessimism, which provides an increased leeway for reflection and the promotion of discussions around faults. This allows for strategies to be improved.

In contrast, pessimism is a serious problem for groups with difficult-to-achieve goals, which is often the case for powerless or under-resourced groups. Even without any outside influence, reflection can convince members that all proposed strategies are futile. Due to this vulnerability, the obligation to avoid anything that would lead to inaction or resignation is felt so clearly that it can feel very awkward to contribute anything that is not in service of optimism or mobilization. This all leads to common phrases like “there’s no more time to think, it’s time to act” and a general disapproval of theoretical discussions. So keenly felt is this taboo against criticism of strategies that sometimes people feel that the only way they can morally justify not partaking in some sort of action is by referencing extreme difficulties in their personal lives, as though they are presenting each other with doctor’s notes.

If a group is defined by a specific type of action, then that group will naturally evade critical and open discussions regarding the benefits of that action as a strategy. Due to this defining characteristic, action being the ultimate good makes perfect sense. They are stabilized by avoiding anything that leads to inaction or resignation; therefore, they’re doomed to incur the costs of this avoidance. This disproportionately affects activity-based groups that are not powerful, or those that are trying to address large-scale problems, which is naturally most groups.

What type of group would not incur the costs of avoiding pessimism?

Optimism of the Will

Groups that are more defined by their vision rather than the actions and strategies that they employ have more room for pessimism. In such groups, one can be disillusioned with every activity or strategy and maintain one’s place in the group. For example, if a member finds that none of the current strategies serves the group’s desired vision, then they can come up with and advocate for new strategies without destabilizing the group's identity. These changes can instead strengthen and build the group. Unlike activity-based groups, members of vision-based groups will so highly value critique, comparison, and exploration of strategies, that this analysis would be included in what is considered as ‘taking action’. Further, such groups seek improvements in their vision and its articulation, which creates room for creative involvement that isn’t judged by how it motivates action.

In practice, groups fall somewhere between the two ideal types provided by this framework. The more a group is limited to specific activities in order to achieve its goals, the more activity-based it is. Conversely, the less that a group is limited in how it achieves its goals, the more vision-based it is.

Vision-based groups are not necessarily more difficult to form, and have the benefit of having fewer constraints. Yet, they are increasingly rare. Why this is the case is an important question that is beyond the scope of this essay. However, the prevalence of more activity-based groups may help explain why attempts to avoid pessimism are so common. Importantly, this interpretation generally explains hesitation towards critical discussion among groups without blaming the idiosyncrasies of the group’s members, their culture, or ideology. It also explains the absence of strategic orientation in many political groups – regardless of the group’s vertical or horizontal organizational structure.

Given the heavy cost of groups being activity-based, it is evident that we need to either build new groups or shift current ones to be more vision-based. In the meantime, we need to admit to the costs of our hesitation and guardedness. They are justified, but we cannot afford them. We need places for us to be when we feel pessimistic. Places where reason, honesty, and exploration do not risk separating us from our social context, where our participation is not judged by how much it contributes to action.

How these spaces are created will be unique to circumstance. In many cases it will need to be sneaked into largely activity-based groups where creating such spaces will receive scrutiny due to the risks they pose to the group. The hope of this essay is to help provide interpretations where we can convince each other that such risks are necessary for us to build stronger communities. The polycrisis of today exists at much higher scales than the scales of the strategies of the groups that we participate with. If our groups are not robust to volatility then, as these crises get worse, the privileged will get to maintain their groups while the rest have to continue re-forming around new tactics and strategies. To build movements of scale, we need to be able to coordinate between groups, an impossible task when groups are frequently formed and re-formed. We need groups that stake their optimism on the belief that we will continue to find a better way forward.

Again that Darwish couplet: "Where should we go after the last frontiers, where should the birds fly after the last sky?"

Yes, exactly. That's the sense of knowing we seem to be at the very last frontier and the very last sky, that there's nothing after this, that we're doomed to perdition - and yet, we ask the question "Where do we go from here?" We want to see another doctor. It's not enough just to be told that we're dead. We want to move on.1

Optimism of the will is when we don’t fear the pessimism of the intellect.

Authors:

Alireza G. Tafreshi (primary)

Eviatar Bach

Jack Montana

Linley Sherin

Roshak Momtahen

Sam Seyedin

Excerpt from “The Pen and the Sword”, a conversation between David Barsamian and Edward Said

Super interesting read that made me reflect on how i approach my own thought process/contributions!

I wonder how this intertwines with Mariame Kaba's assertion of "hope as a discipline". If we are all practicing maintaining and spreading hope, then we are also more insulated to this type of pessimism.

Also, is critique and pessimism the same thing here?

You know, I think we often get pessimism all wrong. We treat it like it's just a bad attitude or a cold, intellectual argument we have to win or shut down.

But honestly, it's so much deeper than that. Pessimism is often just a kind of grief. It's the heavy, aching sadness for all the potential we've lost, the things that failed, or the future that might never happen.

And when we leave that grief unspoken, when we push it down, it warps everything around us. It poisons our closest relationships, and it sabotages the important work we're trying to do as a group.

So maybe groups focused on a big vision don't just need sharp analysis; they need emotional honesty. They need designated moments where it’s actually okay for people to mourn and still keep building meaning.

Think about it: If we can’t stop and grieve together, optimism just becomes a frantic way to avoid the tough stuff. And if we can’t hold on to hope together, that collective sadness just becomes a permanent reason to give up.

The real challenge isn't about picking pessimism or optimism as a permanent side. It’s about building a culture that has room for both, where seeing things exactly as they are and staying emotionally strong aren’t fighting each other. They need to work together in the long, hard process of just keeping going. -Nasr